Maggy Rozycki Hiltner: What Lies Beneath

May 26 2017 - September 16 2017

Maggy Rozycki Hiltner creates textiles that focus on contemporary issues. She combs antique and thrift stores looking for source material, seeking hand-stitched linens and quilts. Her artwork may at first appear whimsical, but on closer inspection reveals a strong engagement with socio-political issues. She ties charged messages into and against the comfortable and innocuous medium of fabric and stitching. Her exhibition at MAM, What Lies Beneath, brings these subtexts to light.

Hiltner’s previous artwork incorporated Dick-and-Jane-style embroidery to tell stories of personal and universal human experiences. Her later work veered away from personal narratives to depict environmental abuses, touching on Hiltner’s Pennsylvania childhood in the shadow of coal, steel, and nuclear energy. She remembers how these hazards found their way into her childhood casually. She grew up within the evacuation radius of the Limerick Generating Station nuclear facility. “I swam in the bathtub-warm water downstream from the power plant,” Hiltner recalls. “The Schuylkill River, once dubbed America’s foulest river, was cleaned up. This meant that coal silt was dredged from the river and dumped in an area we kids called ‘the Black Desert.’ After days riding our bikes there, we had to hose off the black silt before we were allowed in the house.”

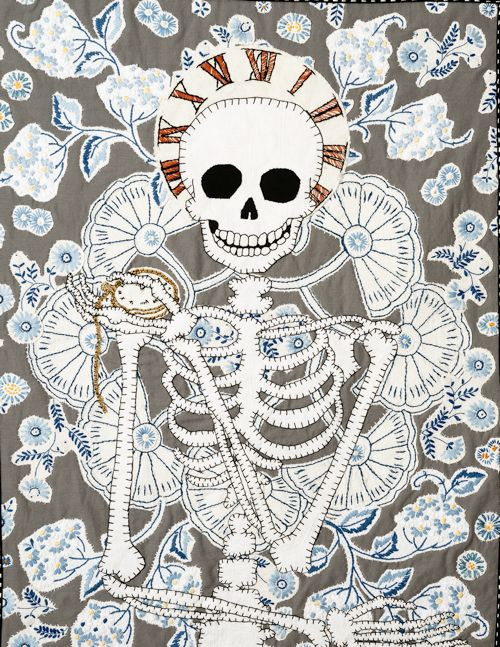

Hiltner still makes work about environmental degradation, not as a cause in and of itself, but as an examination of outmoded, destructive, and unfortunately recurrent ways of thinking. In this exhibition, Hiltner uses the skeleton as a metaphor to point to these mechanisms. With nods to art history and mythology, she questions current events and longstanding tropes.

Maggy Hiltner, Momento Mori (Time), 2016, hand-stitched cotton and linen, found embroidery, copyright the artist.

After considering the design and history of a quilt pattern, Hiltner creates an aesthetic response. For example, in Dresden, she uses a found quilt with the Dresden Plate design (also called Grandmother’s Sunburst or Dahlia), a popular pattern in the 1920s and ’30s. Named for the cultural center of Dresden, Germany, it reflects the Victorian-era fascination with elaborate decoration and the city’s once-flourishing ceramic industry. Allied forces firebombed the city on February 13, 1945, in what is called the single most destructive bombing of World War II—including Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hiltner memorializes this loss of life by dyeing the quilt black and adorning it with appliqué skeletons to resemble one of Dresden’s mass graves—a somber meditation on the human capacity for suffering and destruction.

Requiem employs a found quilt of the Whirling Logs design (also called Catch Me if You Can or Hooked Cross). This centuries-old pattern was an auspicious symbol given in friendship or as a wedding gift, but fell out of favor when the swastika was appropriated by the National Socialist German Worker's Party in 1920. Forever tainted by Nazi association, the quilt is transformed and eulogized by Hiltner’s hand-stitching.

In other pieces, including What Lies Beneath and We Do Not Bury the Dead, We Sow Them, the skeletons, with their collections of bright flowers and ever-present grins, embody change, growth, and perhaps even hope. Hiltner remains reflective, “My hope is that if the image I’ve created feels true, it will transmute for the viewer, evoke a recognition within. Our anxieties, insecurities, joys, and pains are oddly common.”

Maggy Rozycki Hiltner, Requiem, found cotton quilt (Whirling Log), found and hand-stitched embroidery, cotton, 2016, copyright the artist.