Witness To Wartime: The Painted Diary Of Takuichi Fujii

October 1 2020 - December 19 2020

This traveling exhibition focuses on Takuichi Fujii (1891–1964), a modernist painter who left a remarkably comprehensive visual record of his experience during World War II as a Japanese American detainee. Curated by Dr. Barbara Johns, and traveling through Curatorial Assistance, this exhibition is based on her research that resulted in the publication The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness (2017). Fujii was fifty years old and lived in Seattle when war broke out between the United States and Japan. In a climate of increasing fear and racist propaganda, he became one of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast forced to leave their homes and be relocated to geographically isolated incarceration camps.

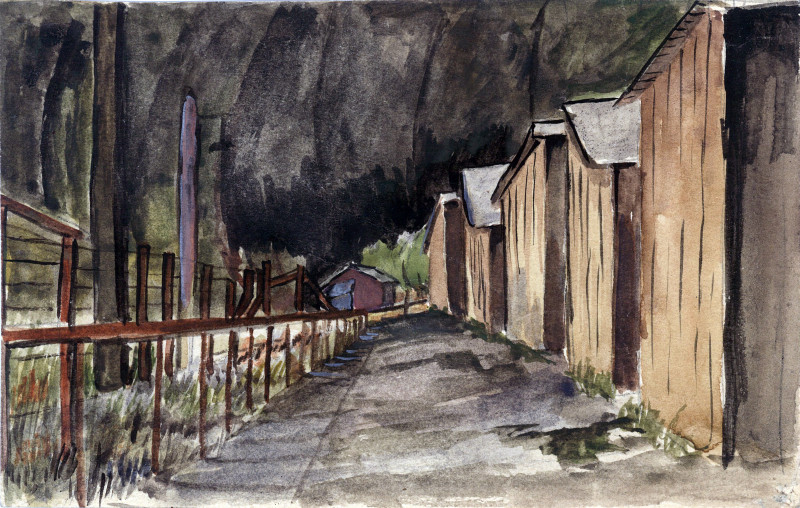

He and his family were sent first to the Puyallup, Washington temporary detention camp and then to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Jerome County in southern Idaho. Fujii began an illustrated diary that spans the years from his forced removal in May 1942 to the closing of Minidoka in October 1945. In nearly 250 ink drawings Fujii depicts detailed images of the incarceration camps, and the inmates’ daily routines and pastimes. He also produced over 130 watercolors that reiterate and expand upon the diary, and several oil paintings and sculptures. After the war, Fujii moved to Chicago, which had become home to a large Japanese American community under the government's resettlement program, where he continued to paint.

This exhibition is presented in collaboration with the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula (HMFM), in recognition of HMFM as an Alien Detention Center during World War II. Looking Like the Enemy: The Issei Internment at Fort Missoula is on view through 2022.

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii is curated by Barbara Johns, Ph.D., and the traveling exhibition is organized by Curatorial Assistance Traveling Exhibitions, Pasadena, California.

This exhibition is supported by a CARES grant from Humanities Montana and generous sponsorship from A&E Design.

Please note no photography of any kind is permitted in this exhibition.

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW featuring Barbara Johns and Brandon Reintjes, senior curator at MAM:

Takuichi Fujii (1891–1964), Minidoka, montage with fence and landmarks, n.d., watercolor on paper, collection of Sandy and Terry Kita, copyright the artist.

Words Matter: Definitions of Terms Used in this Exhibition

Barbara Johns, the curator of Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii, consistently relies on definitions provided by Denshō, a reputable resource on this period in history. If you would like to explore the terms more in-depth, please click here.

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the army to establish military zones from which “any and all persons may be excluded,” targeting, although not naming, people of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast. In the subsequent mass exclusion, the government employed euphemisms to mask the fact that 120,000 individuals were confined without charge, two-thirds of whom were American citizens.

"Evacuation," "assembly," and "relocation" are terms that typically refer to rescue operations. Many contemporary historians use "incarceration" to more accurately describe the conditions in which the majority of Japanese Americans were held involuntarily—behind barriers and under armed guard. This exhibition uses the historic names for the confinement sites and the contemporary usage in descriptive texts.

Describing the experiences of Japanese Americans during WWII with words like, "internment" and "relocation," is misleading and inaccurate. One of the strategies employed by the federal government to forcibly remove and confine Japanese Americans during World War II was the use of euphemistic terms that masked the true nature of what was being done. Japanese Americans were "evacuated"—as if from a natural disaster or for their own protection—from their homes and sent to "assembly centers" and "relocation centers," names that gloss over the fact that these were concentration, prison, or detention camps. The use of the term “alien” was and is used historically to describe foreign nationals, complicated by the fact that many immigrants of Japanese ancestry were denied citizenship, or the fact that land laws in many Western states prevented Japanese immigrants from purchasing or leasing land.

Throughout the exhibition, you may encounter the Japanese-language terms Issei (一世, "first generation") and Nisei (二世, "second generation") to refer to different generations of Japanese Americans. Issei in recognition of their commitment to making their home in America, and Nisei in recognition of their birthright. In addition, Japanese cultural forms made or used in camp became part of “camp culture”—Japanese forms made of materials from the American desert and in response to the specifically American experience of incarceration.

To connect the exhibition to contemporary issues such as immigration or racial justice, visit MAM’s virtual-learning platform, Museum as Megaphone, for more information.

Listen to a presentation by Barbara Johns about the history of Fujii's painted diary:

Related Events: Saturdays with MAM: Virtual programming including mindfulness and an art project related to this exhibit.